Cops are in Crisis. In this History of Policing in North America, France and Britain, we find out why

Over the past year, public anger over police violence has led to calls for de-funding or abolition of police forces. Some even want to police their own communities — which it turns out, is precisely how policing began.

Listen to Part 1 of this 2-part CBC Radio Documentary here or at Ideas

English villages and towns were responsible for their own law enforcement, throughout the Middle Ages. Victims and their families could seek redress directly from the miscreants and mischief-makers themselves. Able-bodied men would “set a watch” and patrol the streets in times of disorder, and monitor entry-points to villages and towns, especially in times of plague.

By the 16th and 17th centuries, that would change. Commoners, who had long been attached to the land, were being liberated — or expelled. High population growth, rising prices for basic goods and a lack of work forced many to travel in search of employment. Large numbers of men were on the move.

“The problem for the authorities was this freedom from their masters, from their lords, looked like ‘masterlessness.’ They were talking about masterless men, wandering around,” Mark Neocleous, professor of political economy at Brunel University in London, told IDEAS.

“They were assumed to be committing crime, assumed to be a political threat, and more than anything they were not engaged in labour for a living.”

To discourage people from being idle, vagrancy laws were introduced across Europe.

“The most policed population from 1500 to 1800 were the mobile poor, the vagrants, the homeless,” said David Hitchcock, senior lecturer in early modern history at Canterbury Christ Church University.

“They come into contact with the law far more often than other non-violent people in early modern Europe. They were seen by the middling and upper classes as lawless.”

Unequal societies

At the same time, commoners were being deprived of ways to live off the land. By the 1800s half of all arable land in England had been privatized, making lands previously accessible for common use, inaccessible. And traditional forms of subsistence were being turned into crimes, said Neocleous. Collecting wood or hunting on private property was now trespassing.

Similarly at the ports, workers were stopped from taking home spilled goods offloaded at the docks, a perquisite— or perk of sorts.

“The custom of taking that commodity as a perk is enabling workers to take goods home for free, and to therefore work less for a wage,” said Neocleous. This too is turned into a crime.

“What this does is impose the wage form on the workers. They are now forced solely to work for a wage. This is massive. And similar practices are taking place in the late 18th early 19th century across a whole lot of other industries.”

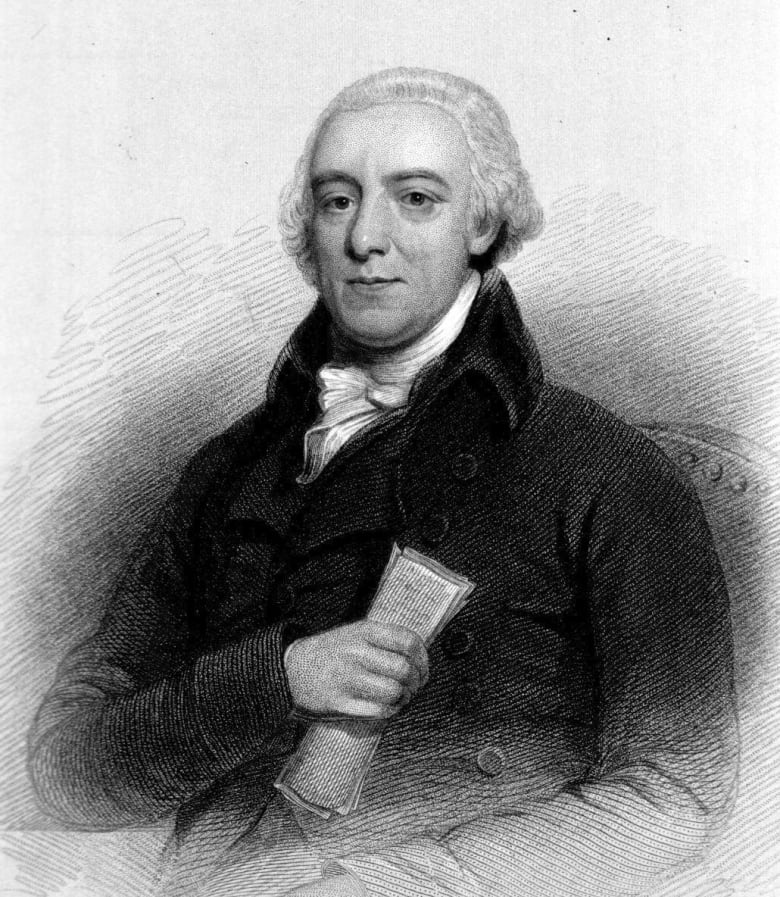

In 1800, merchant and magistrate Patrick Colquhoun — funded by fellow businessmen — set up the River Thames Police, three decades before Robert Peel’s bobbies walked the London streets. Of course, it wasn’t just perks that concerned the elites; widespread theft was a worry at the ports just as it was in Europe’s rapidly growing cities.

An engraving by S. Freeman of Patrick Colquhoun, the founder of the Thames River Police — the first police force in London. (Wikipedia)

“There is a transformation of European societies towards more market activities, towards more unequal societies, and this transformation leads to growing disorders, to rising crime in urban settings,” said Jacques de Maillard, professor of political science at the University of Versailles-Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines and director of the Centre for Sociological Research on law and Police Institutions near Versailles.

“So, the emergence of the police has to do with the transformation of society towards more market-based activities and inequalities and at the same time, the emergence of new public bodies in health, social assistance, but also public order, and regulation of crime.”

Colonial law enforcement leaves its mark

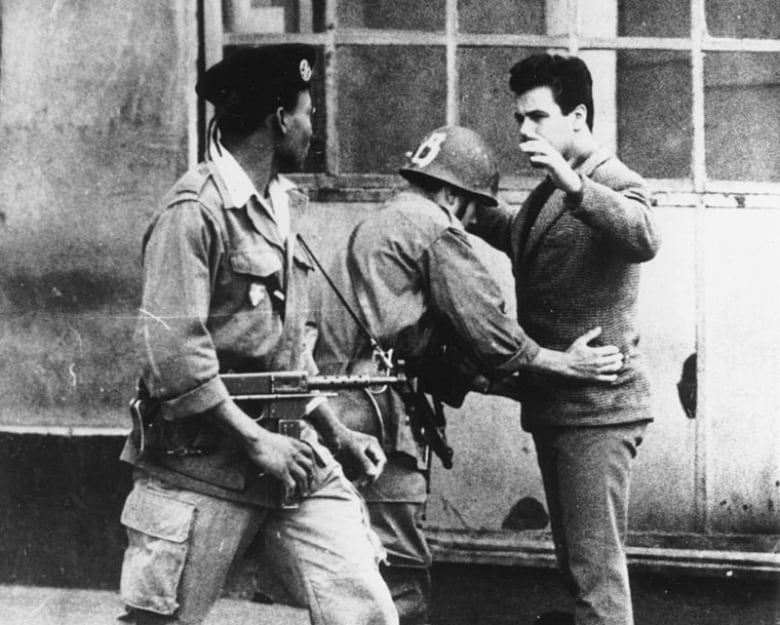

In the same way that urban policing was born out of rapid urbanisation, inequality and rising crime, 19th and 20th-century colonialism made a lasting impact. In France and Britain, surveillance, crowd control and repression methods used in the colonies, were honed and employed at home.

“Colonial troops were repatriated and generals returned to France to shape and influence the transformation of police and law enforcement,” said French sociologist Mathieu Rigouste.

“Colonial doctrines” and tactics, he said, were integrated into French policing and continue to be used against marginalized communities.

Today, immigrants from France’s former colonies are subjected to police street checks in much the same way that those suspected of resistance to French rule in Algeria were in the lead up to independence in 1962.

Several studies have shown that young Black and Arab men are up to 20 times more likely to be stopped by the police in France. Rigouste attributes this to a hold-over from French colonial rule, where the authorities were charged with “pacification” of locals.

Similarly, police have become a kind of “occupying force” in working class, immigrant areas, he said. “So, you have ferocious, provocative units that do identity checks mainly against non-white people, with the aim of finding people without their papers or look for some sort of infraction.”

Over the last decade, French police have been taken to task by the United Nations, the French courts and several human rights organizations for using excessive force.

Lanna Hollo, a senior legal officer with the Open Society Justice Initiative, is involved in three legal cases against police and the French state for discriminatory policing.

In one civil case brought in 2015, 17 young people claim to have been subjected to physical and sexual abuse by police near their public housing complex in southeast Paris. They were aged between 11 and 18 years old at the time.

Last October, a Paris court said the French State was guilty of gross negligence in the affair.

“These police were not looking for crime,” said Hollo. “These police had orders to evacuate public space of undesirables.”

Court proceedings brought to light a police database, which contained dozens of logs referring to “checks on undesirables” in modest neighbourhoods.

“The notion of undesirables has a history in France,” said Hollo.

“At one time, undesirables were Algerians, undesirables were Jews. Undesirables today are young, Black and Arab men in poor neighbourhoods.”

Few cases of this kind have ever reached the courts. Hollo said this is a landmark case, and a form of “collective resistance.”

For police in France as elsewhere, it’s a reminder that they are under scrutiny as perhaps never before.