Paris Attacks one year on: ‘I live with this every day’

Gregory Reibenberg held his wife’s hand until she drew her last breath, assuring her that he would look after their daughter, and himself. Surrounded by dead bodies and shattered tables that had been shot up or thrown aside by people running for their lives, he then closed Djamila Houd’s eyes. After kissing her for a final time, the rest, he says, is a blur.

He happened to be inside his restaurant, La Belle Equipe, in Paris, on the mild autumn evening of November 13, 2015, when gunmen arrived and riddled the patio with bullets, killing 20 people – half of whom were his friends. The rest included regulars, mostly in their 20s, 30s and 40s, from various ethnicities but long-time residents in a culturally mixed and vibrant neighbourhood near the Bastille.

“I’m carrying 20 dead people inside me, and I don’t know what to do”

“I’m carrying 20 dead people inside me, and I don’t know what to do,” he recalls in the notes he took in the ensuing days. “A small tribe was decimated, a team of friends, loved ones, people who make time for each other.”

President François Hollande placed flowers and unveiled plaques at each of the sites of the attacks. Photo by Philippe Wojazer

Houd, then 41, was Muslim, and Reibenberg is Jewish. They worked and lived in multicultural neighbourhoods which stand in stark contrast to the increasingly polarised rhetoric of the French identity politics that have once again taken centre stage.

Reibenberg wrote day and night after the massacre, as though to get the 20 people he carried with him out of his system and onto paper. He had to try – he was now looking after nine-year-old Tess, his daughter, who did not fully understand the finality of the family’s loss.

“Is there any chance she might come back, Papa?” she’d ask.

Reibenberg realised they would both need help. He consulted psychiatrists and began putting into words the lurid scenes of horror that unfolded around him.

Treating a tragedy through writing

Writing as a form of therapy is central to a new clinical study into rehabilitating the survivors, rescuers, families and friends of victims of the coordinated attacks of November 13, 2015. The attack left 130 people dead and many more injured and traumatised.

It is one of several studies being carried out in France to tackle the immense physical, emotional and psychological toll of the events. The innovative project, “Paris Living Memory,” is being coordinated by Alain Brunet, trauma specialist at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, who came to France to launch the programme with Bruno Millet, a psychiatrist at Pitie-Salpetriere University Hospital.

Over six weeks, some 400 participants (currently being selected) will be given a beta-blocker called propranolol, a medication that blocks adrenaline and reduces blood pressure, and helps to prevent traumatic memories from becoming devastating.

Meeting with a psychotherapist, they’ll write a description of their traumatic memories, before reading it aloud and discussing it with the therapist. By repeatedly confronting the memories head-on, patients try to stop memories from culminating in lifelong disorders, like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), by engaging in “memory reconsolidation”.

It’s a treatment that Brunet has been developing for more than a decade, but is now being tested for the first time on a large scale across more than a dozen hospitals in and around Paris.

“When people ‘re-memorise’ a traumatic event while under the influence of propranolol,” Brunet told a Paris conference earlier this year, “they continue to recall the trauma, but the emotional dimension of the event diminishes bit by bit, until the recollection, which at the outset was traumatic, becomes simply a bad memory.”

Specialists will check in with patients three, then 12 months after the treatment.

Another study, called ESPA November 13 examines the physical and psychological impact of last year’s events on victims, witnesses and health professionals to determine how individual and collective memory are affected.

Under psychiatrist Thierry Baubet at Avicenne Hospital, about 1,000 volunteers will be interviewed several times over the next 10 years, to monitor who is liable to develop PTSD, and who recovers more easily.

“We still don’t understand the consequences of these events, especially for healthcare professionals,” says Professor Baubet. “It’s important to know their needs in the ensuing days and weeks, because that’s going to allow us to create appropriate programmes for them in the future.”

A nation in a state of emergency

France has been struck by a series of extremist attacks, from the massacre of journalists and artists at Charlie Hebdo and the shoppers at a Jewish supermarket in January, 2015, to the Bastille Day killings in Nice last July, when a 31-year-old man ploughed a cargo truck into a crowd of people watching fireworks, killing at least 85 people.

The killings have shaken not only those close to the victims, but a nation that has been in a state of emergency ever since.

Reibenberg has a theory about why the attackers struck France. They saw growing tensions between right-wing politicians, populists and one of Europe’s largestMuslim population centres, he says, and sought to capitalise on it.

Hand-written and embedded discreetly as part of the artwork on the restored walls of his restaurant, are the names of the 20 people shot dead on his patio. “Just look at the wall and all the names written on it,” he says.

“You see practically all the nationalities in France!”

Reibenberg’s restaurant, his relationship – a Jewish-Muslim couple – and the socially mixed, multicultural neighbourhood where they worked, were all a standing rebuke to the extremist religious ideology and to the angry anti-Muslim rhetoric of the far-right, which shows no sign of abating six months ahead of the presidential elections.

On Sunday, President Francois Hollande and Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo unveiled commemorative plaques at the sites of last November’s attacks. But for Reibenberg, November 13 is of no importance.

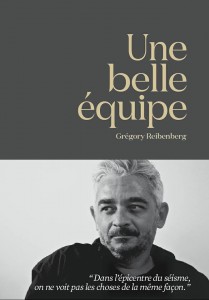

“I live with this every day,” he says, pointing to the back of his head, where his memories sit, bereft of the power they once held. Although he did not participate in Brunet’s programme, writing has been essential for Reibenberg’s healing process and in overcoming the trauma left behind by the attacks. He has all but exhausted his memories, wrung them out on paper until, unexpectedly, he had the makings of his first book – Une Belle Equipe, or A Beautiful Team, which will be out on Monday.

This story originally appeared on Al Jazzera on Sunday, Nov. 13, 2016