The worldwide race to end a deadly epidemic

Scientists and medical experts in more than a dozen countries are racing to develop vaccines to stop the spread of an epidemic that has wreaked havoc in West Africa, killing more than 10,000 people.

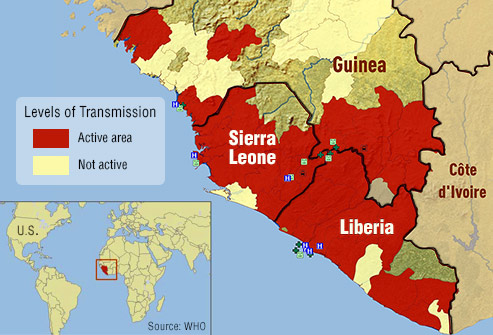

In Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, where the virus has devastated communities for more than a year, many wonder whether a vaccine or treatment will arrive in time.

With a decline in the number of new infections, experts council against premature predictions of an end to the epidemic, and warn of continuing flare-ups, particularly in areas of resistance to anti-Ebola measures.

Towns and villages in Sierra Leone were under a three-day lockdown last weekend, as health workers went door to door offering medical advice and searching for new cases. It’s the latest stage in a battle to contain the biggest Ebola outbreak the world has ever seen.

Enormous resources are being mobilized: at least 15 different vaccines are being tested or developed in hospitals and clinics in North America, Western Europe, Russia and China.

The World Health Organization has identified two vaccines as being most advanced: VSV-ZEBOV, first developed by researchers at Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg and licensed to US drug companies NewLink and Merck; and ChAd3-ZEBOV, developed by the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and pharmaceutical company GSK.

“We have worked hard to reach this point,” said WHO Director-General, Dr Margaret Chan earlier this month. “There has been massive mobilization. If a vaccine is found effective, it will be the first preventive tool against Ebola in history.”

Clinical Trials Unfold in the US, Germany, Kenya, Togo and Switzerland

Much of the work on the two lead vaccines is being carried out in Switzerland. In Lausanne University Hospital, fast-moving nurses bustle down the hall to follow up with volunteers who took part in Phase I of the ChAd3-ZEBOV vaccine trials over the winter. Nurses take blood samples and assess reactions, which a day or two after the jab, ranged from fever to flu-like aches and pains.

“The work we have just done in two months, is usually done in two years,” says Dr. Blaise Genton, head doctor at the hospital’s infectious diseases unit. Like his colleagues in Geneva working on the Canadian-made VSV-ZEBOV vaccine, he and his team conducted clinical trials in record time, thanks to fast-tracked regulatory procedures – and countless extra hours.

“We’ve had to hire new staff, and we all have to work like hell. People are tired. Almost everyone involved in the trial has done a lot of over time.”

Their work has paved the way for vaccines to reach key clinical tests now under way in West Africa, the epicenter of the Ebola epidemic.

In Guinea, some 10,000 people are to be vaccinated over several weeks in a massive clinical trial launched this week by the Guinean government and international partners including the WHO. Results could be available as early as July.

Ring Strategy

Medical practitioners will use what is known as the “ring vaccination” strategy in Guinea, first identifying a newly diagnosed Ebola case, tracing all of the people with whom they have been in contact, and vaccinating each of them in turn, if they give their consent.

This tracing strategy helped eradicate smallpox in the 1970s, and many hope it will slow to a halt an Ebola epidemic that has infected more than 25,000 people across West Africa since the first cases were confirmed in Guinea in March 2014.

From a peak of more than 1,000 new cases per week across West Africa last fall, the number has fallen to an average of fewer than 100 per week.

The declining case numbers, though welcome, have prompted fears that it may be too late to develop an Ebola vaccine in time, and that the paucity of new cases could jeopardize large clinical trials like the one which began testing ChAd3-ZEBOV in Liberia in February. The trials may be transferred to Guinea, where there are larger caseloads.

Too few infections?

Hardest-hit Liberia, with a death toll of more than 4,200 victims, went three weeks without any new cases, before reporting its first new infection on 20 March.

With too few new cases, it is impossible to determine whether the vaccine is protecting volunteers from the virus.

“You cannot test a vaccine for Ebola if there’s no Ebola. You need an active epidemic, which is why there has been such a global collaborative effort to start these trials as quickly as possible,” says Dr. Charlie Weller at the Wellcome Trust in the UK, which has provided about $20m in funding for vaccines, treatments and research.

“In terms of whether we’re likely to get a licenced drug or vaccine during this outbreak, it looks unlikely,” says Professor Jonathan Ball, a virologist at the University of Nottingham.

“Having said that, there are still countries experiencing continuing transmission like Guinea and Sierra Leone, and until people get on top of those cases and bring the totals down to zero, these vaccines – and treatments in particular – get nearer and nearer to being approved and licenced.”

Pockets of resistance to anti-Ebola measures remain, where local distrust of health responders continues to drive up the death toll. Against medical advice, some mourners bury the dead themselves, putting them in direct contact with the virus.

With no vaccine expected for several months, ground-breaking drugs and treatments could help in the mean time. Zmapp, a drug produced by Toronto-based Defyrus Inc. and US company Mapp Biopharmaceutical Inc., releases ready-made antibodies that were raised in the laboratory, in the body, triggering an artificial immune response.

It has already produced extraordinary results. Two American aid workers ill with the Ebola virus in Liberia began to recover after receiving their first dose of Zmapp, though the drug’s role is unclear, as they received other care at the time.

Man suspected of dying from Ebola is sprayed with disinfectant chemicals in Monrovia, Liberia, Sep. 2014

Clinical trials began earlier this month of the experimental drug TKM-Ebola-Guinea, described as ‘blocking certain genes’ of the virus and thereby reducing its replication.

The antiviral drug favipiravir has shown encouraging signs that it could cut mortality rates of Ebola victims who are treated when their symptoms first appear.

As medical professionals scramble to contain the epidemic, fresh questions arise over the role of the UN body charged with coordinating a response to the world’s health crises.

WHO Under Fire

The Associated Press reported last Friday (March 20) that the WHO was slow to sound the alarm when the epidemic first erupted in Guinea last March. AP gained access to internal emails allegedly showing that the UN body “held off on declaring an emergency in part because it could have angered the countries involved.”

WHO spokeswoman Fadéla Chaib counters that the “WHO notified the world of the outbreak on March 23 2014 and at the same time sent supplies and experts to the field, including a mobile laboratory.”

But massive WHO budget cuts prior to the Ebola outbreak are also said to have hampered its ability to respond. Nor did the WHO organise a ministerial meeting on the disease until July 2014 – three months after the virus was first identified.

Institutional Soul Searching

The WHO has since begun some institutional soul-searching. Earlier this month, Secretary-General Margaret Chan commissioned an independent review committee to assess the WHO’s handling of the epidemic. One recommendation calls for a rapid response team including medical professionals and experts in infection control and community engagement, to assess the situation and quickly mobilize resources.

The panel will present its report at the annual World Health Assembly in May.

Governments in the region too, were slow to react, reportedly accusing organisations that sounded the alarm like Médecins Sans Frontières, of causing panic.

Impoverished national health sectors had too few laboratories to test for Ebola and have some of the lowest doctor-to-population ratios in the world. Some communities have been hostile to health workers – in some cases carrying out violent attacks. Educational campaigns have been patchy and belated.

Institut Pasteur in Paris, which identified Ebola’s first victims in Guinea, found that when the government did tackle burial traditions which spread the virus, the impact was immediate.

Early on, funeral ceremonies constituted 15% of all transmissions, along with another 35% at hospitals. Those numbers dropped to 4% and 9% once locals began to conduct safe burials and after a treatment centre was opened.

After a late start, a robust international coalition is now responding with the focus and seriousness that many had hoped to see months ago.

Though the numbers are down, specialists are wary of new flare-ups.

“We cannot claim victory until we get to zero cases,” said Chaib. “One single case means that the outbreak is still on.”