Now Showing in the Theatre of Public Apology

I’m at the local café, glaring across the counter at an increasingly sheepish cashier.

“I can make you another one,” she says, trying to avoid eye contact. She had forgotten I wanted my café latte not up to the rim, but three-quarters up. “No,” I hissed, leaning in, “I want an apology.” My day was already ruined, and only public penance would placate me.

But no sooner was one drama coming to a close, than another began. As I seized my mug from the counter, a woman rudely brushed me as she ran past. She was holding her arm – which seemed badly burned or something – and murmured something about the hospital. But not so much as an “excuse me” as she loped past and out the door.*

These people are oblivious to the fact that our society needs public apologies and expressions of heartfelt regret as much as oxygen itself.

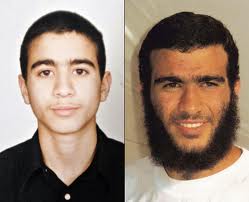

After years of whining about torture, mistreatment and mock justice in Guantanamo Bay, Omar Khadr finally understood: he simply had to apologize.

After years of whining about torture, mistreatment and mock justice in Guantanamo Bay, Omar Khadr finally understood: he simply had to apologize.

The 24-year old confessed to murder, conspiracy and other misdeeds – presumably with the same keenness with which you tend to confess when you’re locked up without trial, deprived of medical aid and given an offer you can’t refuse.

So he pleaded guilty this week for his role in a firefight against American soldiers, during which, at the age of 15, he threw a grenade that fatally wounded Sgt. Christopher Speer.

Standing up to look across the courtroom at Speer’s widow, Khadr duly apologized.

“I’m really, really sorry for the pain I’ve caused your family,” he said. “I wish I could do something that would take away your pain.”

It rivals many of the mea culpas we’ve heard in recent weeks – everyone’s having a go, from government officials to serial killers – but this could ruin Khadr’s career. What self-respecting terrorist cell would hire him now? He might as well pursue a profession in medicine as he told the court, because he just killed the future he had as a top-notch jihadi.

Tabitha Speer was having none of it. She had heard witnesses speak of Khadr being a mere ‘child soldier’ when he was brought to Afghanistan by his father. No, she said, “the victims are my children, not you.” Indeed, they read victim impact statements – just like in real court. The jury – members of the US military, sure to examine the case with judicious equanimity – wept at the heart-rending testimony.

Word of the emotional courtroom scenes had even reached the Middle East, where aspiring terrorists are said to have broken down in tears.

Apparently one was on his way to a crowded market, bombs strapped neatly across his chest, when the news came up in a podcast on his headphones. He stopped mid-step, and turned to enter a Shisha café, where he smoked a pipe and re-considered his whole take on the U.S.

True, no trial is about to prosecute the US military for the thousands of civilians it’s killed in Iraq and Afghanistan. But that’s because the tearful tales of victims’ families there could hardly match the quality we’re seeing in Gitmo – even if we account for translation.

From what I understand, an editorial board picks the best stories.

US authorities then gently question the suspects, while the courts begin selecting juries and star witnesses.

Tabitha Speer’s eight-year old son concluded his emotive letter thusly: “Army rules. Bad guys suck.”

No son, the army doesn’t quite rule, but it gets more column inches. While American soldier deaths are counted meticulously, the dead in Afghanistan and Iraq are uncounted, and unknown. As we hear of the heroics of “first class” soldiers, and the sadness of the families they leave behind, men, women and children in countries crushed by the American war machine, suffer in obscurity.

Save the apology, Khadr. Do something that seems so hard for those addicted to the histrionics of contrived contrition. Start building a new life – quietly.

******************

*NOTE: Some scenes are exaggerated or invented entirely. The scarcity of satire in the Canadian media compels me to spell it out.