Could they be the Future Leaders of Africa?

JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA — They have had a hand in changing national legislation in Kenya, built a school for refugees in Uganda and synthesized fuel from natural waste in South Africa — and they’re not even in university yet.

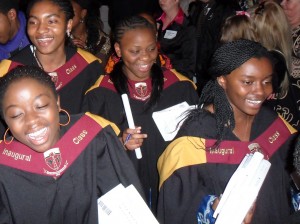

This summer, they became the first graduates from the African Leadership Academy, which has drawn students from 33 African nations.

For 19-year-old graduate Joseph Munyanbanza, the academy’s rolling lawns are a world away from the refugee camp in Uganda that has been his home since he was six years old.

He fled there with his older brother to escape civil war in the Democratic of Congo — then Zaire — eventually reuniting with their parents in the camp. As a young boy he had no shoes and read by a fire at night to get ahead in his makeshift studies.

He says the two primary schools there were ill-equipped, the teachers underpaid and unmotivated, so he tutored younger children and obtained funding to build a new primary school.

“The success created another big problem,” he says, “because they wanted to go to high school — but there wasn’t one in the camp.”

Munyanbanza found a secondary school in a neighbouring town that charges no fees, and rented a house for the kids.

“What he has done at 17 is more than most people do in their lifetimes for society,” says Fred Swaniker, who co-founded the academy to cultivate what he says is in desperate shortage in Africa — strong political and entrepreneurial leadership.

By recruiting young talent and teaching a combination of practical courses in ethics and entrepreneurship, and preparatory courses for university, the academy hopes to create 6,000 leaders in politics, business and the social sectors over the next 50 years.

“Imagine what they could do if you gave them an opportunity to come to an institution like this,” says Swaniker, “and connected them to the right networks so they could take the ideas and the potential they have, and scale them up.”

On graduation day in the large auditorium, students unveil projects to the excited applause of friends and family: they’ve developed a new student online banking system, a maths program on DVD and a face cream that repels mosquitoes to combat malaria.

South African 19-year-old Spencer Horne explains what he’s working on: a digester for a school kitchen.

“It breaks down whatever waste they’ve got and turns it into methane gas, along with other by-products which can be used as fertilizer afterwards,” he says. “Once it’s complete we’d like to see them cutting down the cost they’re currently spending on gas for cooking.”

The academy is recruiting high-achieving youngsters from all over Africa. In Kenya, Tabitha Tongoi was a junior minister in the Children’s Parliament, which lobbied the government to make trains safer for children. Kids were often squeezed out of packed carriages, and forced to walk long distances or sit on the roofs of moving trains. Now trains have designated children’s carriages.

For her community project at the academy, Tongoi raised 10,000 books for kids in Nairobi’s informal settlements by seeking donations from more privileged students.

“People were burning their books once they were done in high school,” she says. “Yet right down the road, someone else would really need these books. So that was basically my role, just as a bridge between the ones on the left and the ones on the right.”

Already armed with sizeable CVs, academy graduates are just getting started. Many of them are leaving to study at universities all over the world, including Oxford, Duke, Harvard and University of Toronto. (While some students were offered scholarships, others were not, and can’t afford to accept offers of admission outside of Africa.)

Here is the Music Player. You need to installl flash player to show this cool thing!

The scholarships that allowed most students to study at the academy have one key condition attached: it’s a forgivable loan, as long as alumni return to Africa for 10 years or more after finishing university. If they remain abroad, they must repay the loan.

It’s the academy’s attempt to stem Africa’s brain drain, by which thousands of professionals leave the continent for job opportunities and higher pay, every year.

Large numbers of African doctors and nurses work in Europe, the U.S. and Canada. Adrian Gore, CEO of South African financial services firm, Discovery, said, “more than half of the doctors that graduated (in South Africa) since 1980 are now working abroad.”

According to the Network of African Science Academies, as many as one-third of all African scientists live and work in developed countries.

Horne, who will study engineering at Harvard, sees no need for the academy’s contractual clause.

“It’s true, I could probably walk into an easy job after graduating and make lots of money immediately,” he says, not lacking confidence.

“But I think I’d derive a lot more satisfaction from being involved directly, from innovation, and helping out. I think that’s really important and it’s more exciting, really.”

The hope is that graduates return to maintain the momentum of Africa’s economic and political development, which has accelerated over the past decade. Between 2000 and last year, Africa’s economies have grown on average by more than 5 per cent — far outpacing advanced economies.

And with some infamous exceptions, more African countries are holding free and fair elections and are more politically stable than a decade or two ago.

But these improvements will remain patchy unless there’s a move from immediate, hand-to-mouth aid toward longer term investment in education, says Swaniker.

“You can invest in feeding kids for six months, but after those six months they’re hungry again. That cycle will never stop until you create an amazing scientific leader to improve crop yields so that the community can feed themselves forever,” he says.

“Or we can spend millions of dollars treating the refugees that come out of a war, but that won’t stop until we have leaders who don’t go to war in the first place. So the investments we’re asking people to make in these leaders is to stop these problems once and for all.”