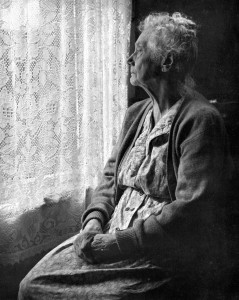

Trust and Betrayal in the Golden Years

GLOBE AND MAIL

Saturday, January 27, 2007

Just when they’re needed most, a growing number of children are turning on aging parents — taking away their nest eggs and their independence. But as KYLE G. BROWN reports, getting justice is no easy task.

Concerned about her mother’s mental health, Sarah took decisive action. She helped 82-year-old Celia move to a retirement community, she set up accounts for her at a local health-food store and an upscale clothing boutique. She also took over her financial affairs.

But at the mention of her daughter, Celia says: “I swear to God, she should be in jail.”

Since 2004, when an Alberta court granted her daughter guardianship of her mother and control of her $400,000 in savings and stocks, Celia claims Sarah has taken almost all of her possessions — and left her without a bank account, or even identification. (Both of their names have been changed to protect their privacy.) While her daughter claims to be acting in her best interests, Celia feels betrayed and helpless.

And she is hardly alone. Toronto lawyer Jan Goddard, who has worked on elder-abuse issues for 17 years, says financial exploitation of seniors is now “endemic across the country.” This can range from snatching a few dollars from grandma’s purse to transferring property.

Brenda Hill, the director of the Kerby Rotary House Shelter in Calgary, agrees. “We’ve had people who have had their homes sold, who have been virtually on the street with no food and no money because their children have taken all their assets,” she says. “It happens quite often.”And the problem is likely to get worse before it gets better. People 65-plus are the fastest-growing segment of the Canadian population — but cuts to health services in the 1990s have meant that fewer seniors are living in public institutions.

This, in turn, has placed increased pressure on family members, which a Statistics Canada report in 2002 suggested could lead to a rise in the abuse of older adults.

South of the border, taking money from mom and dad is also seen as a serious issue. So much so, that the Elder Financial Protection Network predicts that it will become the “crime of the century.”

Ageism is partly to blame. As is a culture of entitlement — where the money parents spend can be seen as a “waste” of the child’s future inheritance.

Charmaine Spencer, a gerontologist at B.C.’s Simon Fraser University, says both are particularly prevalent in North America. Although she adds, “I have not seen a single culture in which abuse of the elderly does not take place — it’s financial and psychological abuse, and when that doesn’t work, it’s physical.”

But addressing such exploitation is anything but straightforward.

How do legal and medical professionals determine when adult children are taking advantage of aging parents — and when they are enforcing necessary restrictions on those no longer able to care for themselves? How do they intervene, either to stop abuse or to help elderly parents cope with newly dependent roles, when seniors are enmeshed in painful power struggles with grown sons and daughters?

Take one of Ms. Goddard’s eightysomething clients. The increasingly frail woman complained that she needed more support than her son — who lives in her house — was providing. She decided to revoke his power of attorney.

But, according to Ms. Goddard, when the woman told her son about the meeting, he was furious. The next day, she called Ms. Goddard to cancel everything. As she spoke nervously on the phone, Ms. Goddard could hear the woman’s son in the background, telling her what to say.

Though lawyers like Ms. Goddard can call in the police in such situations, getting seniors to make formal complaints against their children can be difficult. Ultimately, she says, clients have to face the repercussions of confronting their families and “keep wavering whenever they go back home.”

Seniors’ own shame can also keep them from reporting that their children are taking advantage of them. Although abuse seems to cut across socio-economic lines (even New York socialite Brooke Astor made headlines recently because of her son’s alleged neglect), older adults often feel guilty talking publicly about private matters.

As for those who do brave action against their children, many do not make it very far. While money is in their children’s hands, victims of financial abuse cannot afford the fees to take a case to court — which can run at a minimum of $10,000. And legal aid is rarely awarded to seniors involved in civil cases.

Ms. Hill tells the story of a Calgary widow who sold her house and moved into her daughter’s home. Her children transferred money from her account to theirs, borrowed her bank card and charged her for “services” such as rides and errands.

A few months later, the woman fled to the Kerby Rotary House Shelter with a small fraction of her savings. But at the age of 87 she could not face the idea of spending what little time and money she had left in the courts. Now, she resides in a seniors’ lodge with just enough cash to live out her days — though her daughter will never az screen recorder premium apk be brought to justice. Dr. Elizabeth Podnieks, the founder of the Ontario Network for the Prevention of Elder Abuse, conducted the first national survey on elder abuse in 1990. She says that even when lawyers do take seniors’ cases, complainants have difficulty convincing the court that they are the victims of theft and exploitation. For example, their memory is often called into question, as they struggle to recall “giving” money to defendants.

Family members who question their parents’ ability to look after their finances may consult a capacity assessor — a health professional with special training in assessing mental capacity.

Tests vary from province to province, but Larry Leach, a psychologist at Toronto’s Baycrest centre for geriatric care, says they generally set out to answer the tricky question of whether elderly adults “appreciate all the risks of making an investment and giving gifts to people.”

If a parent is deemed incapable, the government may then become the guardian of property until a family member applies to the courts to gain guardianship.

This is what soured the relationship between Celia and her daughter.

In 2004, Celia was diagnosed with dementia and deemed “unable to care for herself.” Her daughter then won guardianship over Celia’s affairs.

Celia hotly disputes the doctor’s findings — but now the onus is on her to prove that she is mentally fit or to appoint a new guardian.

Meanwhile, she is no longer speaking to Sarah. Once in charge of her own health-food store, she feels humiliated taking “handouts” from her daughter. “I can’t do anything. Where can I go with no money?” she says.

As for more cut and dried cases, where neither dementia nor family dynamics is in play, Dr. Podnieks says: “Older people don’t understand why the police can’t just ‘go in and get my money back.’ They know it’s a crime, you know it’s a crime, the abuser knows it’s a crime — so where is the law, where is the protection?”

Detective Tony Simioni, who is part of the Edmonton Police Force’s Elder Abuse Intervention Team, says senior abuse is about 20 years behind child abuse, both in terms of public awareness and government and police resources. “Financial-abuse cases rarely see the top of the agenda,” he says. “It’s low on the totem pole of crimes.”

Still, Judith Wahl, who has been working at the Advocacy Centre for the Elderly in Toronto for more than 20 years, remains optimistic. She believes that public education campaigns on elder abuse are making an impact. The rising number of reported incidents, she says, is partly due to a growing willingness to talk openly about abuse.

A 75-year-old Winnipeg woman is a case in point.

She was coerced for years into paying her daughter’s bills, rent and grocery tabs.

“I would come home and cry and sort of tear my hair, and think, ‘Where do I turn to for help? Who do I go to?’ ” she says.

But eventually her friends encouraged her to contact a seniors support centre. With their help, she gained the confidence to confront her daughter — and to grant her son power of attorney.

These days, she gives gifts to her granddaughter, but when her daughter asks her for more, she tells her to talk to her “attorney.”